Relatively few Westerners are known to have been in Isfahan between 1590 and 1602.

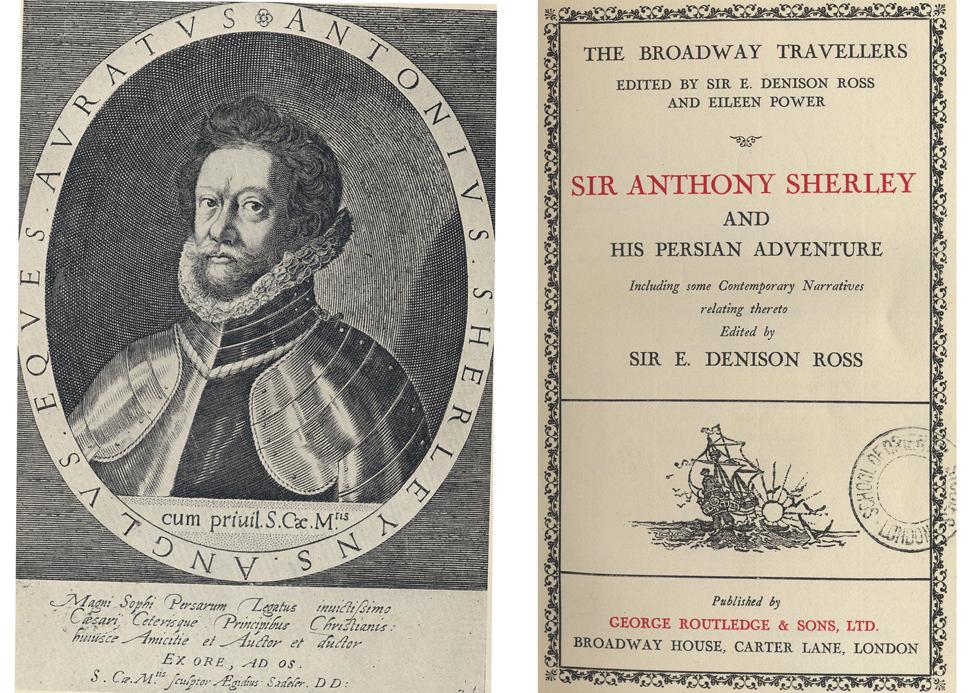

The notorious Sherley brothers and their party did, however, visit in 1599. Their story was certainly popular: it was considered interesting enough to appear in at least four English versions before 1602. Translations appeared in French and Spanish, and Anthony Sherley rehashed his “prolix and pompous” pronouncements in 1613[1]. Elements of the tale were dramatised – most famously in Twelfth Night (1601/2), but also in The Three English Brothers (1607)[2]. Extracts were also included in early modern England’s two major compilations of travel narratives: Hakluyt and Purchas[3].

The Sherley party spent several months in Isfahan[4], but although they declared the place a “famous city”, they seem to have spent their time on “hawking, hunting, and other sports” rather than in making detailed observations or even in engaging in simple sightseeing[5]. The maydan in Isfahan was not specifically described. All the various accounts were focused more on (European) political objectives and personal aggrandizement (especially of Anthony Sherley), than on empirical reporting[6].

This was not because there was nothing to say. John Cartwright visited Isfahan shortly after Anthony Sherley left[7] and provides an eventful description of the “At-Maidan, which is the greatest marketplace or high street of Hifpaan [sic]”. Cartwright provides details of Abbas’ morning routine of visiting his stables and his armourers, and writes of how, at three in the afternoon, the Shah usually “makes his entry” into the maydan, where:

“are erected certain high scaffolds where the multitude do sit to behold the warlike exercises performed by the King and his courtiers, as at their running and leaping, their shooting with bows and arrows, at a mark both above and beneath, their playing at tennis [actually polo], all which they perform on horseback with diverse more too long to write of. In this place also is to be seen several times in the year, the pleasant sight of fireworks, of banquets, of musickes, of wrastlings, and of whatsoever triumphes else is to be showed for the declaration of the joy of this people”[8].

Matthee has written of how the seventeenth-century travellers “represent a unique moment in the history of alterity” – no longer moralistic missionaries and not yet omniscient imperialists[9]. Cartwright certainly fits into this mould – indeed he is something of a pioneer[10]. In contrast, the Sherleys, with all their political, religious and financial problems, were – had to be – more self-interested: they spent their lives “covering their tracks”[11]. The accounts by members of their party had specific objectives, and therefore different outcomes than straightforward observation[12].

[1] These have been winningly described as appearing “rather to have in view the display of [Anthony’s] own superior talents and profound sagacity, than the information of his readers on the minor points of his route”. Anonymous, “The Travels of the Three Sherleys,” Review of The Three Brothers; or the Travels and Adventures of Sir Anthony, Sir Robert, and Thomas Sherley, in The Oriental herald and colonial review V (1825), 690.

[2] John Day, William Rowley and George Wilkins. The Travailes of the three English Brothers. SirThomas, Sir Anthony, Mr Robert Shirley. As it is now play’d by Her Majesties Servants. London: George Eld, 1607. This was most likely commissioned or at least supported by the Sherley family.

[3]Ema Vyroubalová. A New and Large Discourse on the Travels of Sir Anthony Sherley. Accessed Jan 3, 2013.http://www.ucd.ie/readingeast/essay2.html

[4] Robert and some other members of the original party stayed behind when Anthony left with the 1599 Persian embassy.

[5] George Manwaring. “A True Discourse of Sir Anthony Sherley’s Travel into Persia,” in Sir Anthony Sherley and his Persian adventure, including some contemporary narratives relating thereto, ed. Sir Edward Denison Ross. (London: G. Routledge & Sons, 1933), 214 and 222

[6] Parry, for example, emerges as a “skilled and dedicated advocate of Anthony Sherley”. Vyroubalová. A New and Large Discourse. Richard Wilson provides a detailed context for the Sherleys in “When Golden Time Convents: Shakespeare’s Eastern Promise”. Accessed Jan 3, 2013. http://www.societefrancaiseshakespeare.org/document.php?id=1502.

[7] Anthony’s fame was such that Cartwright flagged up that his Preachers Travels included “a true relation of Sir Anthonie Sherleys entertainment [in Persia]” by noting this in the title page.

[8] J.C. [John Cartwright], The Preacher’s Travels, wherein is set downe a true Iournall … (London: Printed for Thomas Thorppe, and are to be sold by Walter Burre, 1611), 66.

[9] Matthee, “The Safavids under Western Eyes,”141

[10] Cartwright was the first Englishman to visit all four key sites of antiquity in the Near East (Babylon, Nineveh, Persepolis, Susa). Kenneth Parker, Early Modern Tales of Orient: Critical Anthology (Routledge: London, 1999), 106

[11] Richard Wilson, “When Golden Time Convents”.

[12] Matthee, “The Safavids under Western Eyes,” 152.