Iskandar Beg Munshi’s History of Shah Abbas is in perhaps surprising contrast. The author was in the personal service of the Shah[1] and has come – “somewhat by default” – to be seen as “authoritative”, particularly with reference to the replanning of Isfahan after it was decided to make the city the capital[2]. However, Iskandar Beg’s chronicle includes very little information specifically about the maydan: “Of that which [Shah Abbas] built in Sifahan [sic] [there included] … a marketplace around the maydan with apartments above …”[3].

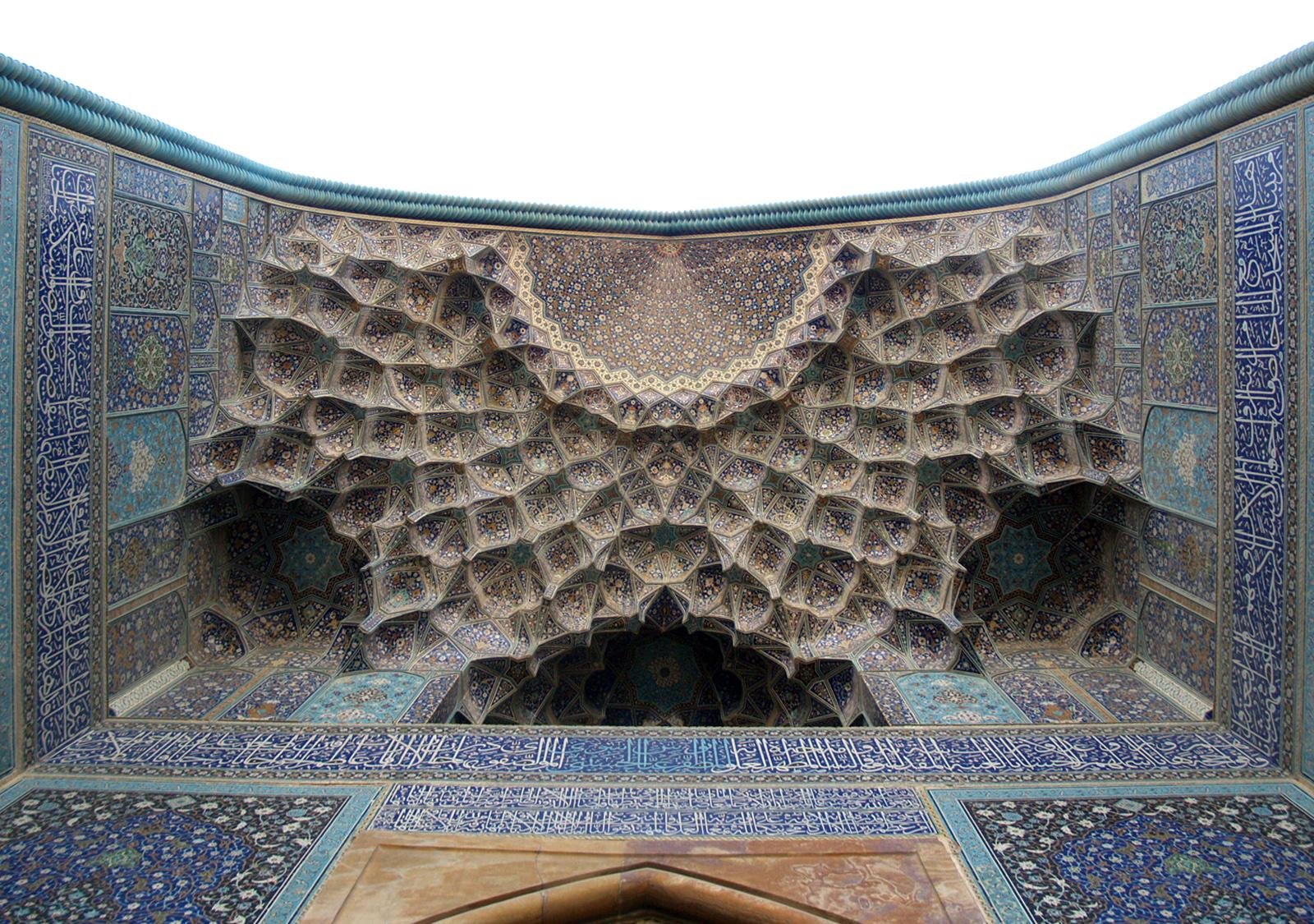

Instead Iskandar Beg concentrates on the Chahar Bagh and the Masjid Shah (constructed on the southern edge of the maydan)[4]. The writings of Safavid courtiers “offer a carefully constructed, idealized portrait”[5]. Does Iskandar Beg’s focus represent a distinct chapter in the history of the maydan – as the monuments developed to symbolise the breadth of Abbas’ imperial, commercial and religious triumphs? Perhaps it was simply that the huge space of the maydan was no longer a novelty, while the Masjid Shah was a recent project – it was still under construction when the first section of the History was completed in 1615[6]. After all, as McChesney points out, it is difficult to imagine that those Persians who wrote histories (and praises) of Shah Abbas would be “any less likely to record the splendour of Isfahan than were foreign visitors”[7].

Like the other Persian authors considered here, Iskandar Beg’s descriptions of Isfahan invoke paradisial references: the water channels were shaded by cypress, linden, juniper and pine trees; and the precincts commanded “the envy of the garden of Paradise”[8]. There were also pre-Islamic references: the legendary palaces of Khwarnaq and Sadir were said to be mere “tokens” next to the “wondrous” buildings constructed for and by Shah Abbas’ favourites along the Chahar Bagh[9].

[1] Iskandar Beg joined Shah Abbas’ personal service in 1592/3. Natanzi and Junabadi were also bureaucrats. Jalal-i Munajjim was a favoured court astrologer.

[2] Robert McChesney, “Four Sources,” 105.

[3] Robert McChesney, “Four Sources,” 112.

[4] Robert McChesney, “Four Sources,” 111-12.

[5] Matthee, “The Safavids under Western Eyes,”151

[6] Ali Qapu was elevated by 1615 (though it was still then without the talar, which was completed in 1644). Lotfollah was completed in 1618/19.

[7] Robert McChesney, “Four Sources,” 103.

[8] Robert McChesney, “Four Sources,” 111.

[9] Robert McChesney, “Four Sources,” 111.