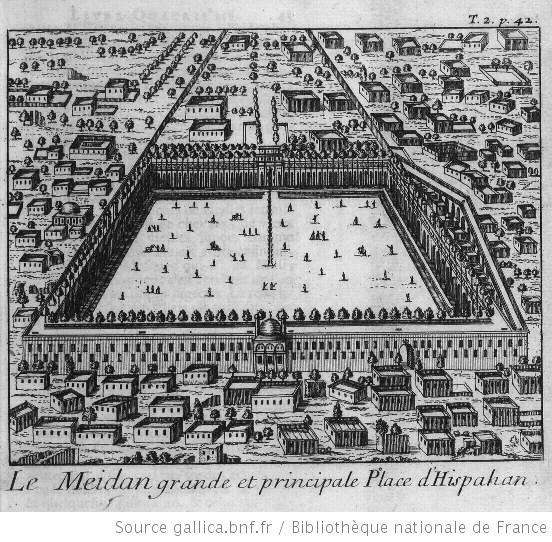

I have tried in this part of the website to give a flavour of the impressive maydan that Shah Abbas imagined within the Safavid architectural ensemble in Isfahan.

Archaeological and textual sources make it clear that this maydan was constructed in two distinct phases: first in 1590 and then, over a decade later, in 1602. This is the era when Western travellers started to travel more frequently to Persia. It is therefore possible to look at the symbolic image of the maydan as pictured by those Westerners, and even to compare it with the image disseminated by Persian writers.

I have concentrated on the earliest accounts, as reflecting the period when the maydan was literally constructed. I have tried to focus on those Western authors who helped to form the symbolic image of the maydan: referencing those most swiftly published, and the most popular – as determined in terms of re-prints and altered editions.

Of course, each author had different reasons for writing, and these affected their output in diverse ways. The Persians were official or semi-official court chroniclers, and so were expected to venerate Shah Abbas and his doings. Fulsome description was one way of doing this. The Western authors, if they wanted to sell their books, had to fulfil the expectations of the contemporary market. It is perhaps easier to look critically at their attempts to observe, and to condemn their “little reading”– than it is to appreciate the limitations in our own knowledge about their background, or to comprehend how our own modern scholastic background affects our own reading of their writings.

All of the sixteenth/seventeenth century authors used comparisons and, especially, superlatives in describing the maydan. The Persians most commonly mentioned the Quranic Paradise; while the Westerners lauded the maydan’s massive size (even if they couldn’t measure it accurately) and mentioned the symmetrical, orderly disposition that has, paradoxically, been suggested as conjuring up the secure Safavid polity for the Persians. The case study here of the Royal Exchange hints at the Western context, as well as exploring a locale that was used as a comparator for the maydan by several Western authors.

The Persian sources, especially, emphasise the dynamic status of Safavid Isfahan. In direct contrast to the Orientalist static trope, and the inert – if stylish – image that modern visitors see, the maydan was in an active state of development throughout the reign of Shah Abbas. This dynamism echoes the huge strides that the Shah made: transforming an anarchic land overseen by conflict-ridden war-lords and over run by all its neighbours, into an internally peaceful and internationally successful Empire. No wonder that Paradise was invoked.

Westerners usually had a limited understanding of the architectural changes that had occurred in the maydan, let alone the religio-socio-political revolution that it mirrored. The changes in the successive editions of Herbert were less representative of the changes in Isfahan and more about the motile nature of early modern European literature and the element of self-fashioning in the accounts of seventeenth century authors when they wrote about Iran.

In this short section, I have focused on the shops, workshops, and apartments that formed the backbone of the maydan. Although I have not been able to pursue this idea in the limited space here, I have wondered whether the monumental buildings embedded in its periphery, evoking as they did the various internal, imperial and religious triumphs of the Shah, represented additional phases in the development of the maydan.

The formation and several transformations of the maydan were key elements in the making of Isfahan into a throne-worthy capital. The Western visitors may have interpreted the maydan’s immensity, and the slanted perspectives of the surrounding monuments, in different ways from the Persians. Everyone, though, understood the architecture as that of a ‘City of Rule’.