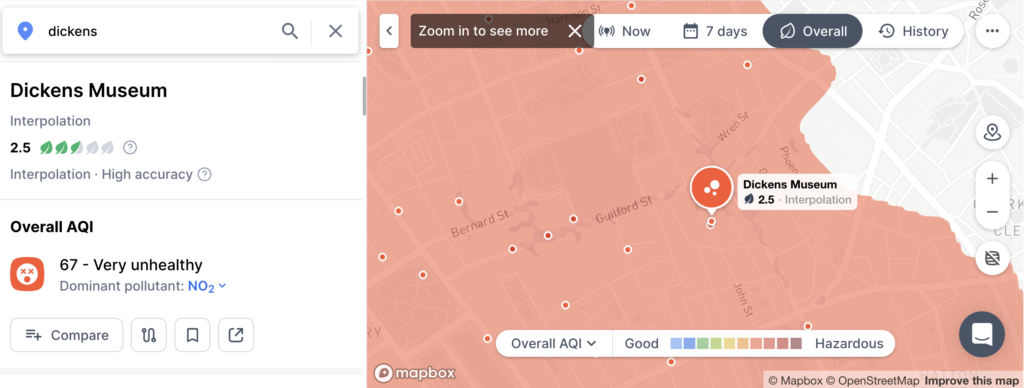

Our London Climate Action Walk air quality walk ended at the Dickens Museum – on the left above:

Image above right shows the nearby Airscape monitor – results below:

This location was partly chosen because of the dirty air exhibition on there at the moment.

Bleak house was set in the dense dirty fog of Victorian London:

Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes — gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun.

There’s lots of great exhibits in the show, but I’d like to pick out two.

First, a beautiful lace handkerchief. It’s surely a version of protective Covid masks.

Look how fine and white it is!

In practice, coverings like this quickly got grey in the famous pea-soupers.

And the fog meant real problems getting round.

We drove slowly through the dirtiest and darkest streets that ever were seen in the world (I thought) and in such a distracting state of confusion that I wondered how the people kept their senses.

For me, the confusion described here feels really similar to nonsense climate denial , and the similarly-nonsensical ‘miraculous’ thinking approaches to eg carbon capture and ‘sustainable’ aviation fuel.

More positively, the Dickensian darkness apparently also meant real opportunities for Victorian couples to meet secretly.

[image]

I’m also – and especially – interested in the dust heaps of Our Mutual Friend.

They were very close to the route of the LCAW walk.

And dust from them surely must have blown into the Bloomsbury area.

The Wilfer family – key characters in Dickens’ novel – lived:

… in the Holloway region north of London […]. Between Battle Bridge and that part of the Holloway district in which he dwelt, was a tract of suburban Sahara, where tiles and bricks were burnt, bones were boiled, carpets were beat, rubbish was shot, dogs were fought, and dust was heaped by contractors.

Here’s an 1837 watercolour of the Great Dust Heap. It’s on the site of what became King’s Cross station. The trees in the background are in the grounds of the smallpox hospital.

A later label described that the Heap was “removed in 1848 to assist in rebuilding the City of Moscow, Russia.”

This: “provides a clue to the commercial value of the dust mound, which, comprised largely of fine cinders and ash, was sold on as material for the manufacturing of bricks (in this case, exported to Russia) as well as to farmers for manure. The cinders and ash were collected from London households by dust-contractors equipped with both the means to transport dust and a plot of waste ground on which to deposit it, working under contract from local parishes.”

In July 1850, shortly after the removal of the Heap, Richard Henry Horn published an article in Dickens’s journal Household Words, titled ‘Dust; Or, Ugliness Redeemed’. There’s more detail of dustheaps and the people working on them in Somerstown here: http://www.crht1837.org/join/draft-history-page/before-the-railways/dust-heaps

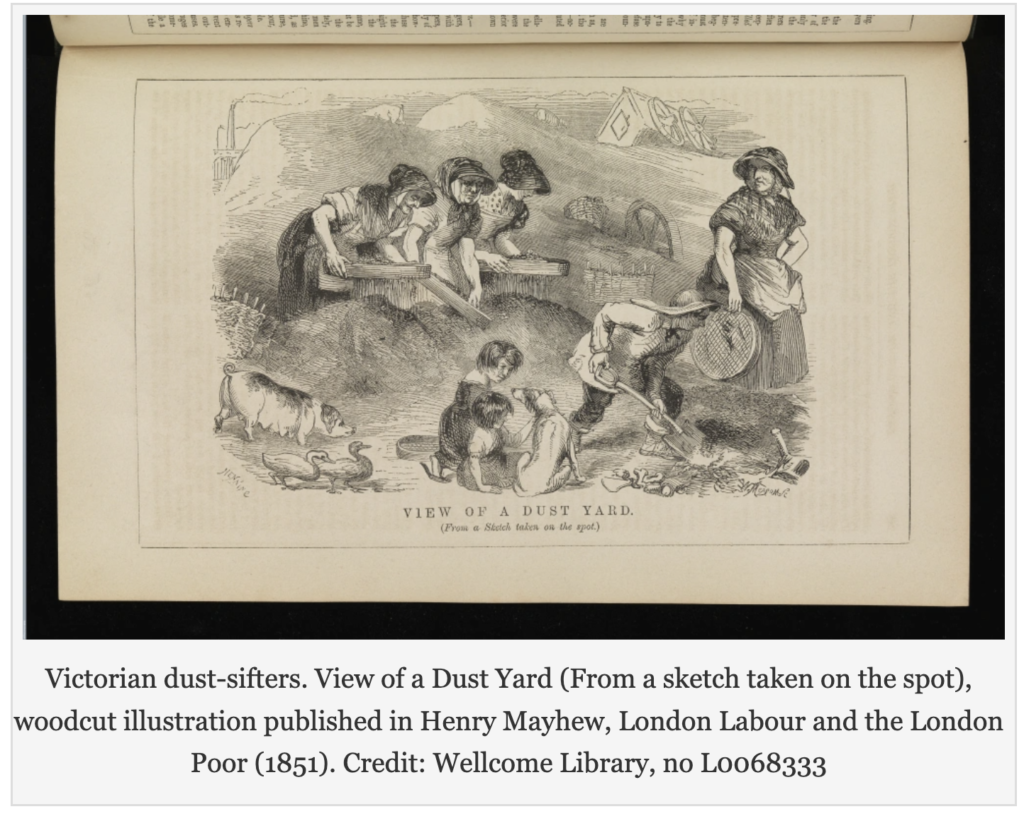

Women, children and old men – ‘sifters’ or ‘scavengers’ – spent their days on the dust heaps with a sieve separating out the components. Here’s a description:

They were almost up to their middle in dust…in front of that part of the heap which was being ‘worked;’ each had before her a small mound of soil which had fallen through her sieve… The appearance of the entire group at their work was most peculiar.”[6]

Its very similar now: there are clear links between inequalities and air pollution: “communities which have higher levels of deprivation, or a higher proportion of people from a non-white ethnic background, are more likely to be exposed to higher levels of air pollution.”